The word underrated is often used about Róisín Murphy – she’s not keen on it. Though the Irish singer has a better command of pop absurdity than most actual pop stars right now – and has influenced everyone from the outlandishly dressed Lady Gaga, to the smooth, disco-inflected music of Dua Lipa – her full impact still flies under the radar, shaping dark underground basement clubs as much as the highest echelons of pop.

When Murphy moved to Sheffield aged nineteen, she began getting regular buses to Manchester’s cultish queer night Homoelectric, the city’s ‘exotic disco for homos, heteros, lesbos and don’t knows’. Unlike the city-centre gay bars pumping iffy trance and chart pop remixes, Homoelectric was a home for eclectic house, italo disco, techno, and weird, amorphous dance music that didn’t quite fit anywhere else – in the spirit of the New York clubs that first shaped disco in the 80s.

These misfit nights out also shaped Murphy’s solo music, and eventually she became part of the institution. Alongside the likes of Hercules & Love Affair, Horse Meat Disco, Todd Terje, Midland and Robyn, her music featured heavily on the Homoelectric soundsystem – and when the night returned as all-night festival Homobloc last year, Róisín Murphy was a standout from the bill. Today, her influence is visible across the LGBTQ+ dance community in particular: you can hear flickers of her 2007 dance track ‘Overpowered’ – and the punchy Boris Dlugosch remix of ‘Sing It Back’, her biggest hit with trip-hop group Moloko – from the likes of Honey Dijon, The Blessed Madonna, and San Francisco DJ crew Honey Soundsystem. Asked about her level of fame earlier this year, Murphy commented to the Irish Times that “if I wanted to be famous… I can go to a gay club.” And like a true gay icon, she added that her status means she can still “go to Tesco”.

And it’s this hedonistic, neon-strip lit atmosphere that Róisín Murphy references with her new lockdown 2.0 live-stream, successfully harnessing the energy of a night out – sometimes accidentally. When Mixcloud’s website breaks in truly colossal fashion during ‘Narcissus’ (the stream returns around 15 minutes later) it’s ironically the closest that 2020 will ever come to a speaker suddenly blowing in the DJ booth, and a silent room quickly filling with overhead lights and dramatic whoops.

Her show itself has the vaguely chaotic energy of a live-band club set in the IKEA flat-pack section, but with an eerily cavernous feel. Rather than attempting to replicate the communal pulse of the dancefloor, Murphy continually draws attention to its absence – as she emerges from a scarlet-hued plastic curtain and paces theatrically down the warehouse aisles during opener ‘Jealousy’, camera crew glide silently past on wheel-mounted trolleys, and a stage tech calmly unfurls a microphone wire as she gyrates atop a ladder. A lone dancer has a solo-shimmy to ‘Something More’ while facing a screen broadcasting Murphy singing elsewhere in the giant industrial building: a smart and subtle nod to the disconnected medium. Later, the pair unite, embrace, and roll around on the floor during a decadent live arrangement of ‘Flash of Light’ – Murphy’s 2012 track with Luca C & Brigante. For the closing two tracks, they’re inseparable, and skip along hand-in-hand.

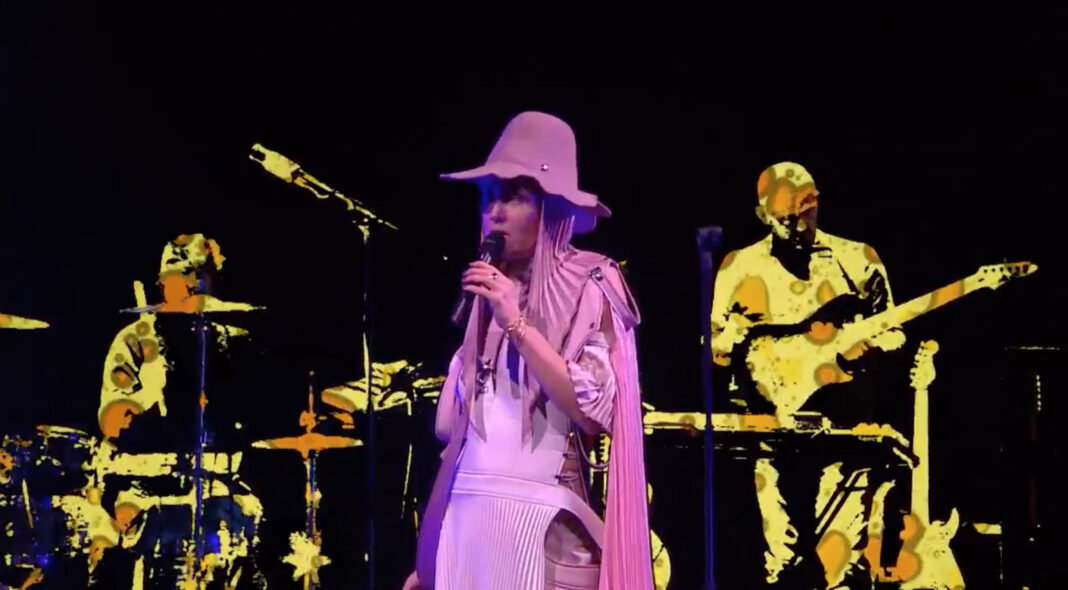

While this performance’s bizarre backdrop remains constantly in focus, the pandemic won’t stop Róisín Murphy throwing an outrageously cracking party with multiple costume changes: along the way we’re treated to a resplendent pirate hat, a giant pink snood that resembles a cheerleader’s pom-pom, and a yellow-and-white fluffy number with a wide brimmed hat so large it drapes over Murphy’s entire face. Set-wise, the biggest bangers from recent album ‘Róisín Machine’ get aired alongside some reworked rarities: several Moloko songs (‘Forevermore’, ‘Cannot Contain This’, ‘Familiar Feeling’) feature alongside ‘Golden Era’ – her track with former Club Zanzibar DJ and deep house pioneer David Morales. Visually, it’s stunning and ever-shifting.

And its two of these less well-aired tracks – ‘Golden Era’ and ‘Familiar Feeling’ – which are most affecting. Rather than ending with a soaring climax, the live band set down their synthesisers and return with acoustic instruments – the screen shifts to display a sofa, as if looking outward. Murphy and her band dance in procession through the warehouse. “Is this my world disappearing? I can’t believe just what I’m seeing,” Murphy sings, presciently “and if you go where does that leave me?”. As the metal warehouse door slowly lowers to ‘Familiar Feeling’ Murphy presses her face up against the glass window, and thumps it with her fist. “Nothing can come close,” she sings insistently. With all the pounding bass and bright lights all taken away, it’s a quietly moving, comedown from an exceptional performance: and a reflective reminder of what we’re aching to experience again.